Bed checks in the 60s: Women-only curfew at USF

While today’s students couldn’t dream of being told to be in their dorm by 1 a.m. on a Saturday night, it was the norm for USF’s female residents to have nightly bed checks in the 1960s.

This was at a time when off-campus apartments were practically non-existent. Students were required to live in dorms and students who did want to live in an off-campus house had to live with an approved supervisor.

Women would be required to be in their dorm by curfew each night. RAs were responsible for bed checks and calling students who were not back in time.

Students leaving the dorms would have to inform the front desk of where they were going and leave a list of phone numbers of the people they would be with.

Sophomore communications major Callie Macinnis said she and her friends share their locations when they go out, but that having a curfew is too restrictive. Macinnis had mixed opinions about the curfew.

“That’s weird,” she said. “I understand the safety part of it, but also, it shouldn’t be in a controlling way.”

Arielle Estrill, a freshman health sciences major, said she couldn’t imagine having to be in her dorm by a certain time every night because she works in the evenings. Because of her work schedule, she said she needs to be able to get back to her dorm at later times.

“I’d have to be able to work and then also have the freedom of when I can get back home too,” Estrill said.

Curfews for female students were common across Florida universities, including the University of Florida and Florida State University. It served as a way to protect students, but had political and societal causes.

Related: Vandalization and protests: The little-known history of MLK Plaza

When students went off to college, the university had to prove to parents their child would be safe. Even though college students were legal adults, their parents and the administration had a strong grip on disciplining the young adults.

“Why do women specifically have to be in their dorms by a specific time, but men don’t have to?” Estrill said. “It just seems like it’s a constriction on the freedoms of women.”

One of USF’s few co-ed dorms had metal doors dividing male and female sides. There may have been some tapping, flirtation and “playfulness around these doors that kept everyone apart” after curfew, according to Andy Huse, USF’s Special Collections librarian.

The curfew was so restrictive that when the power went out, only male students were allowed to leave the building. This prompted women to open up their windows and shout at the men standing on the lawn by the building.

Related: Are you Date-A-Bull? This early 2000s dating site allowed students to find their match

In 1967, the curfew was extended until 2 a.m. The later curfew gave women a few extra minutes to get back from their nights out in St. Pete, but many of them were already back before the clock struck 2 a.m.

In 1967, Margaret Fisher, USF’s former dean of women, said the curfew “met the intended purposes very well.” She also said the only complaints she had received were from men. Some male students wanted curfew as an excuse to leave bad dates early. Others were annoyed that their neighbors were coming back late.

Macinnis said the men using the curfew as an excuse was “crazy.”

“Sorry, they had to man up and actually talk about their feelings instead of just being like ‘Oh, no. Curfew. Sorry,’” Macinnis said.

However, women reportedly appreciated the extra hour.

Related: Nostalgia: Picasso at USF? It was more likely than you think

When off-campus apartments did start popping up around campus in the late 60’s, some advertised their buildings had no curfew, such as La Mancha Dos Apartments.

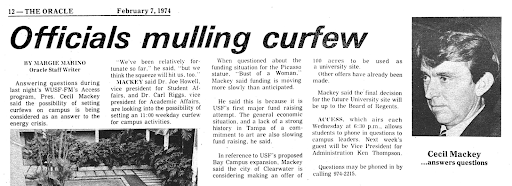

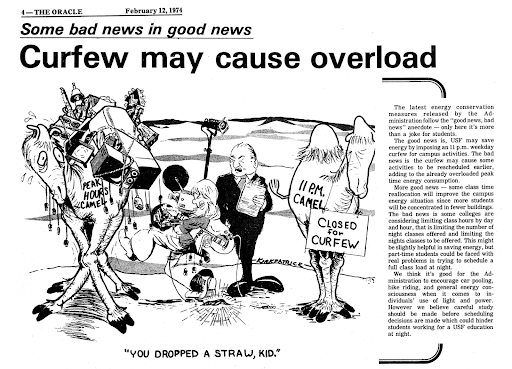

In 1974, the country was experiencing an energy crisis. Tensions in the Middle East had cut off a large source of U.S. oil and there was pressure for energy conservation. In February, then-USF President Cecil Mackey began discussing an earlier curfew around 11 p.m. in response.

Under the newly proposed curfew, university-sponsored activities would have to end by 11 p.m. on school nights and by midnight on Friday and Saturday.

Estrill said the curfew was unfair and likely not the best solution during the energy crisis. She said she thought the administration could have come up with more efficient solutions.

The curfew aimed to conserve energy drew mixed reactions, with some saying it would help and others arguing it would add to the “already overloaded peak time energy consumption,” according to a February 1974 Oracle article.

Theater-goers and performers appealed the curfew, saying shows did not end until 11:30 p.m. and they could not start any earlier than their 7 p.m. start time because “people need to eat,” according to another February 1974 Oracle article. Theater programming directors feared the curfew would force them to cut the number of films they showed.

By April 1974, Mackey was feeling the pressure from students who were calling to “Dump Mackey,” according to an Oracle article. He announced the 11 p.m. curfew would be repealed for weekend movies.

Mackey eventually ended the curfew at USF when the energy crisis was over around this time, according to Huse.