OPINION: DeSantis’ war on education is a prelude to tyranny

I use the word “war” advisedly. In my lifetime, it has been applied metaphorically to any number of policy initiatives, beginning with President Johnson’s “War on Poverty.” The same metaphor has been employed, defensively, by those decrying a purported “War on Christmas.”

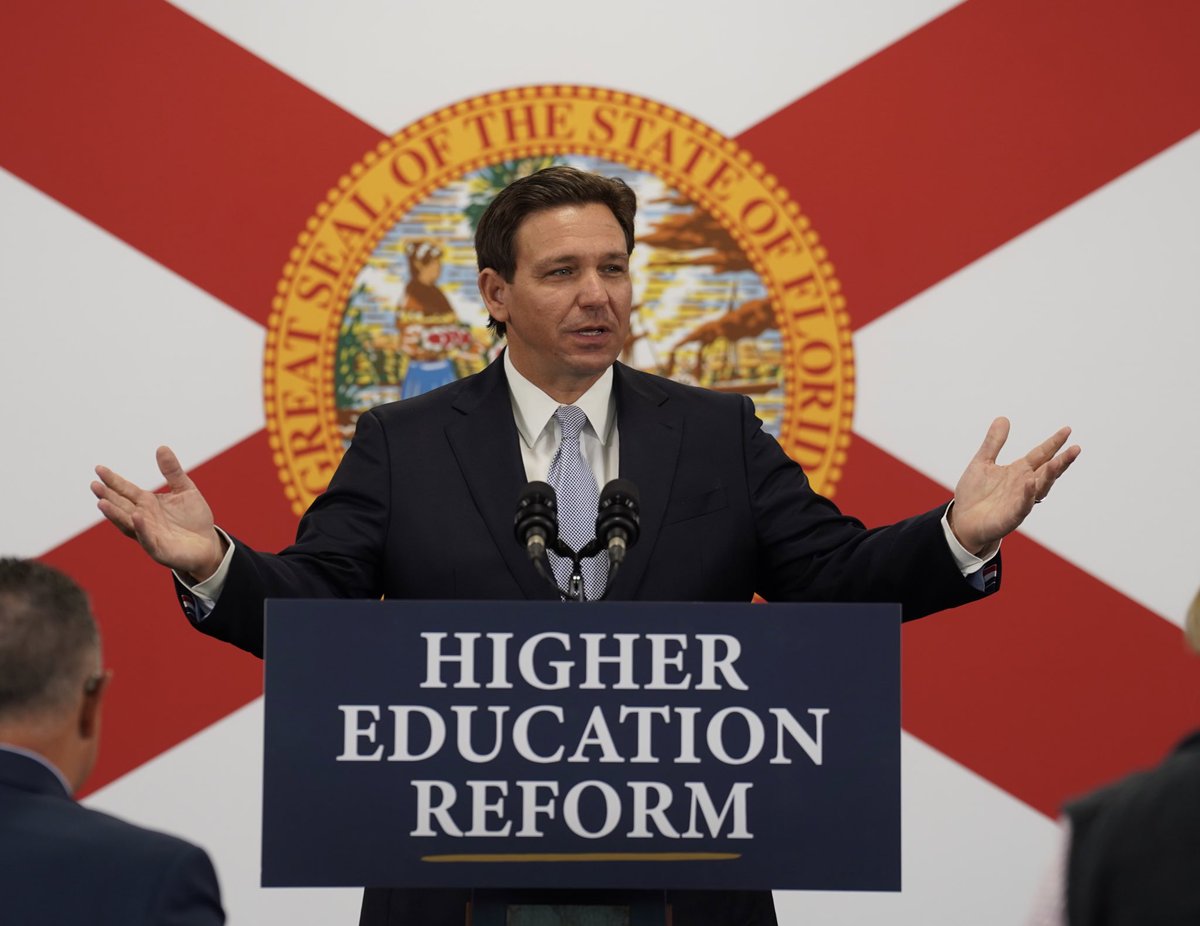

Whether offensive or defensive, a war mobilizes a society like nothing else. It is in this sense that, as I shall argue, Gov. Ron DeSantis is waging a war on public education in Florida, and on higher education in particular. Though the war is metaphorical only, like any other such initiative it can have very real casualties, among them your own chances of earning an education worth having.

“There’s really a debate about what is the purpose of higher education, particularly publicly funded higher education systems,” DeSantis said in a Jan. 31 press conference.

As an educator, and one employed by and devoted to Florida’s public system of higher education, I would welcome such a debate. Unfortunately, far from engaging in it or even encouraging it, the governor has consistently opposed such debate, while seemingly assuming that it has already taken place, and that its outcome is a foregone conclusion.

When he first assumed office, it would not have been reasonable to assume that the Governor, a product of Yale and Harvard, knew anything about publicly funded higher education systems, in Florida or anywhere else. In the years since, he has had every opportunity to inform himself, perhaps by speaking with university students or faculty not pre-selected for compliance with his preconceptions.

That he has not availed himself of such opportunities is a choice. It is both easier and more politically expedient for him to caricature our system as riddled with divisive ideologues, imaginary leftists bent on indoctrinating Florida youth into hating their country and each other, than to pay even cursory attention to the work we actually do.

For example, the Governor has asserted the need, in opposition to what he calls “the dominant view, which I think is not the right view, to impose ideological conformity, to provoke political activism,” to instead “ensure higher education is rooted in the values of liberty and western tradition.” This would require teaching the “actual history and actual philosophy that has shaped western civilization.”

I chair the Department of Philosophy at the University of South Florida. We are completely committed to teaching “actual philosophy,” including that which “has shaped western civilization.” I myself regularly teach PHI 2010, or “Introduction to Philosophy,” one of the state-wide humanities core courses approved by the Florida state university system.

My own syllabus is as conservative as it is possible to be. It is heavy on the “classics,” from Plato and Aristotle through Kant and Mill – most of them works I myself studied in my first year in college nearly 40 years ago. This being the case, one would think that, if anyone in Florida higher education approved of the Governor’s initiatives, it would be me.

That I do not approve of them is because I recognize them as fundamentally misguided. As I teach the texts I assign in Introduction to Philosophy, I also think about them very carefully, just as I encourage my students to do, regardless of the particular beliefs they might bring to the table.

My approach to this class differs in numerous ways from those of my colleagues, as it should; a range of approaches to material is a good thing, even when that material is part of the western canon. If there were no room for debate about what a canon is, whether and why it matters, and what its contemporary significance is, then there would be little point in continuing to study it.

I cannot speak to what DeSantis might have learned at Yale or Harvard, but he seems to have missed this point. It is not a difficult one to make. In Plato’s Apology, Socrates defends the value to his society of his regular critical confrontations with fellow citizens, uncomfortable and embarrassing though they were. Famously, Athens executed him for speaking freely. That Athens was wrong in doing so is a judgment those who have aspired to free societies have shared ever since.

We study the example of Socrates not because he is a dead Greek who lived a very long time ago, but because of his contemporary significance, as acknowledged in Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

“Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half-truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal,” King wrote. “We must see the need of having nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men to rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood.”

As a teacher of “actual philosophy,” I have found myself returning frequently to one lesson learned from Socrates: freedom is not something a society can attain and, having attained it, rests on its laurels. Freedom is aspirational, and aspiring to it demands that we question authority, or as King put it, “to a degree academic freedom is a reality today because Socrates practiced civil disobedience.”

The continued relevance of the classics of western civilization – texts I love and will continue to teach as long as I am able – is demonstrated in multiple ways; for us, for example, it is demonstrated by African American history. It is reaffirmed by our willingness to continue to engage, critically, with our received conceptions of race, with the realities of racism, and with the possibility, however remote, that as Americans and Floridians we might do better.

To offer such claims up for consideration — as worthy of discussion at a Florida institution of higher learning — is not to indoctrinate, or to enforce ideological conformity. But I suspect the Governor knows as much. As a means of social control, a witch-hunt has the advantage that one can never prove there are no witches, any more than I can prove that there are no zany leftist ideologues at Florida universities, though I have never personally met one.

A witch-hunt is a low-risk strategy for those in power, as is caricaturing, misrepresenting and villainizing those who have no effective way of fighting back, any more than a state employee can effectively fight the Governor.

Again, none of this comes as a surprise to the student of western philosophy; as Plato showed, the primary weakness of democracy is its propensity, under unscrupulous leadership, to collapse into tyranny.

Alex Levine is a professor and chair of the department of philosophy at USF.