Stopping students before they drop out

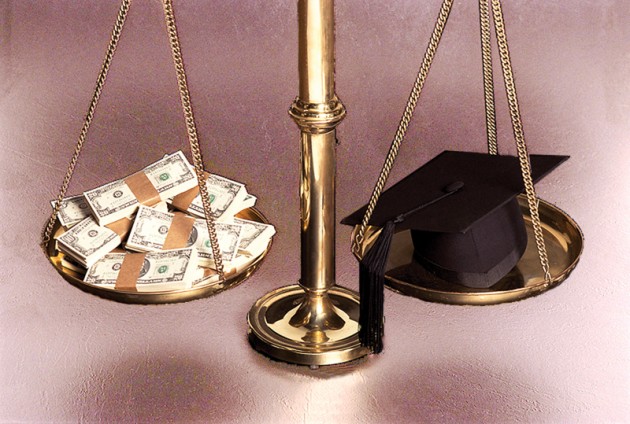

Unemployment. Eviction. High gas prices.

For some students, these aren’t just symptoms of a weakening U.S. economy — they’re things that make getting by financially so difficult that they consider dropping out of college.

To help students overcome financial difficulties and stay in school, USF recently launched a program that provides help beyond a financial aid check.

The Web site and counseling program, called “Don’t Stop, Don’t Drop,” help students tap into well-known resources — such as federal loans — and provides emergency assistance, and may later branch into payment plans for on-campus housing.

“Don’t Stop, Don’t Drop” is designed to “help students when they are about to make that life-changing decision: ‘Should I stop?’ or, ‘Should I drop (out of college)?'” said Les Miller, director of the Office of the Student Ombudsman.

The program does not provide any new financial resources, but Miller said a major problem is that students do not take advantage of resources already available to them: About half of the students who have called program counselors had not filled out the application for federal financial aid.

A big part of the program is telling students what’s available to them, he said.

Housing and Residential Education has agreed to examine extenuating cases to determine if students might benefit from a payment plan to cover their housing costs, said Carmen Goldsmith, who worked with Miller to develop the program.

Miller hopes to provide emergency housing for short periods to students facing eviction, and said he is trying to secure an agreement with Aramark — which runs the school’s dining facilities — to provide food in cases of similar emergencies.

The program, which took a month to develop and launch, was President Judy Genshaft’s idea, said USF spokesman Michael Hoad.

She saw a need to create this program during a meeting in Washington, D.C. about university budget cuts, he said.

Part of the program’s goal is to help students get organized and use resources already in place at USF, Hoad said.

“A lot of times, these students are unlikely to seek help,” he said. “Let’s reach out to those people.”

Hoad said the program is also an internal message to University faculty and staff, so they can help students navigate through offices and departments that can seem overwhelming and complicated.

“The school isn’t really out there saying, ‘Hey, this is what’s available to you,'” said Elana Goldstein, a junior majoring in English education.

Goldstein, who works full time, said items like books are becoming more difficult to afford for her and her friends.

Sabrina Leandre, a junior studying bio-medicine, said that things that affect many students, such as the cost of gas and food, are making it increasingly difficult to stay in school. Though she lives 10 minutes from campus, her weekly gas bill sometimes exceeds $50.

Officials from the University of Central Florida and Florida State University said that those universities have not implemented similar programs. Instead, they direct students in need to existing financial aid offices.