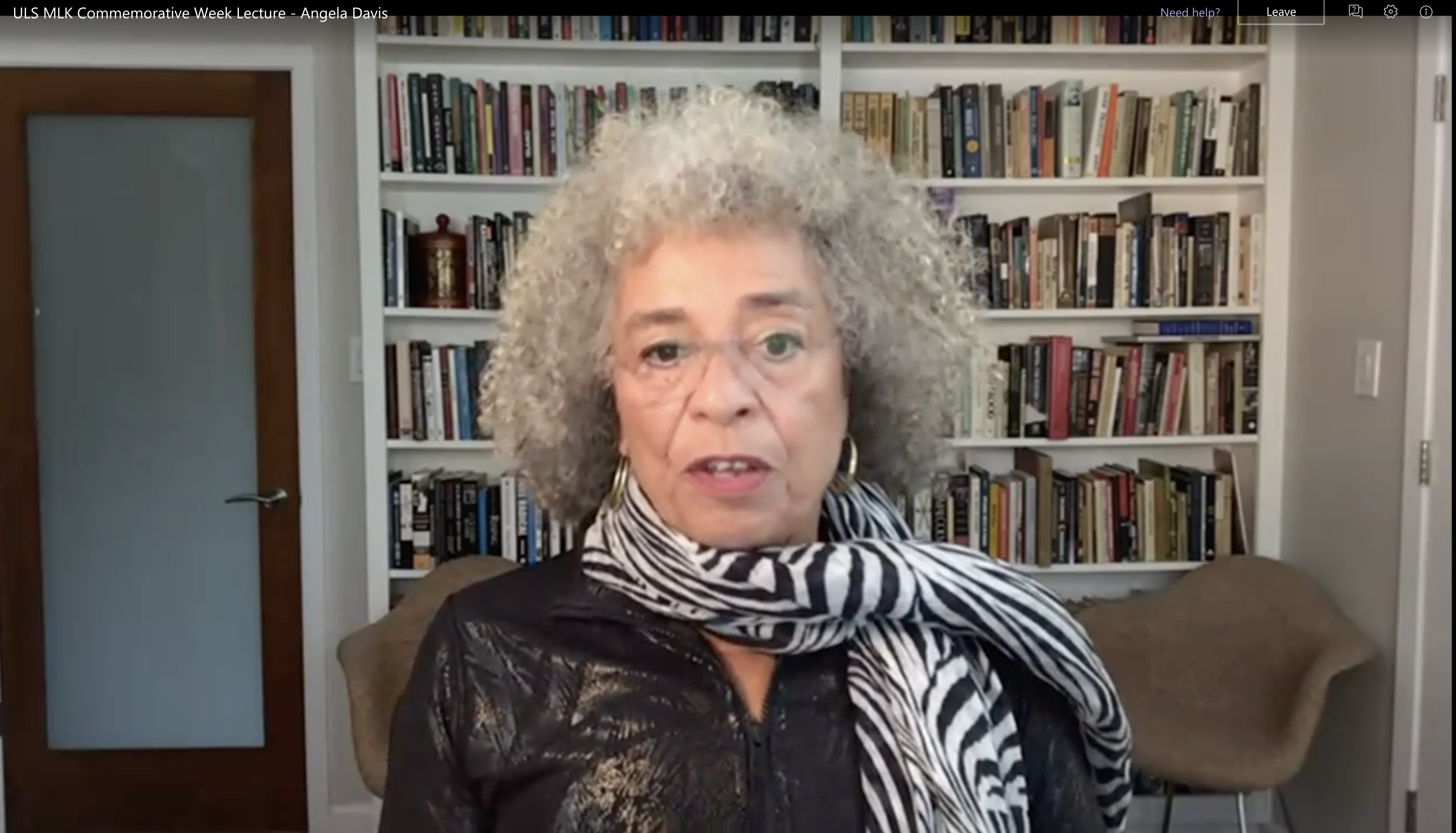

Angela Davis critiques capitalism, systemic injustices during ULS

As a young girl, Angela Davis would run across the street from one neighborhood to another with her friends, attempting not to be caught trespassing into a white-sanctioned neighborhood. Back then, she didn’t know that one of the house steps she would run onto belonged to a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

“Black people were not allowed to be present in the white neighborhood, unless they had an economic reason for being there. I must say, domestic servants were allowed to be there,” she said.

“It was illegal for us as Black people to cross the street, but we’d only dare the children to cross the street, so we actually developed some games in which we dared each other to run across the street and run up the steps of a house where we live and learn a Klansmen lives.”

While living under a segregated society, Davis fought against systemic racism without even knowing it.

Born and raised in a segregated city in Alabama, political activist Davis experienced oppression and prejudice throughout her life as she fought to dismantle segregation. Her scholarly endeavors have since been dedicated to dismantling the system that she referred to as the “status quo” at Thursday evening’s University Lecture Series (ULS).

Davis learned early in life that questioning the conditions in which she was born was needed in order to succeed in a society that she believed to be ruled by white supremacy.

“The reality that was given to me did not necessarily have to be accepted as a personal reality,” Davis said in reference to the systemic racism of the 1940s and 1950s.

The most eminent topic of the lecture was the intersection between racism and capitalism. She said capitalism cannot be dismantled due to it being ingrained in every aspect of society, including the global economy.

“We know that it is not possible to bring the whole system down,” she said. “We can develop a critical awareness that allows us to make connections with the work that capitalism is constantly doing, not only on the institutions that we rely on, but also on our own.”

Davis also expressed doubt in the new Biden administration. She is uncertain in its ability to take initiative in condemning the incarceration system, which would mean involving itself in the abolitionist movement, a common call to action by racial justice activists since the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

“I have to remind myself to be critical. Simply because there is a Black woman in that office does not necessarily mean that we are moving in a progressive direction,” Davis said. “And that if we’re going to take advantage of the recent electoral developments, we’re going to have to strengthen our movements and be willing to get out there and mobilize and organize against the people we support.”

Abolitionism was originally the movement created to end slavery in America, but now refers to getting rid of the racism that occurs within the prison system, according to Robert Boneberg, chair of the abolitionist organization Free the Slaves.

Davis does not believe that President Joe Biden or Vice President Kamala Harris will work to defund the police despite their endorsement of the recent Black Lives Matter movement, which promotes the defunding of America’s police system.

“There is the question of abolition. That question that we raised over and over again, and I don’t think that either of the new people who are in the White House, the executive branch, president vice president, are going to, by themselves, move in the direction of defunding the police,” Davis said.

Davis’ involvement in the abolitionist and feminist movements was also a prevalent topic of discussion during the ULS. She described the importance of feminism and abolitionism in racial justice activism.

“Feminism is relevant to everyone. The kind of anti-racist, anti-capitalist feminsim,” Davis said. “The kind of abolitionist feminism, that I think can help bring change.”

Davis’ association with the abolitionist movement intersects with her ideology pertaining to the importance of education. She believes that education is integral to being an activist and critiquing the modern incarceration system’s effects on inmates and minorities.

“Knowledge gets produced behind bars,” Davis said. “And I always emphasized the fact that … those of us who are involved in the abolitionist movement know [that our knowledge of the incarceration system] has its roots in the intellectual work of prisoners.”

Highlighting her experiences with other social justice activists, Davis said knowledge not only comes from education but through other aspects of life, both of which are intrinsic to liberation from racial and sexual oppression.

“One can utilize education towards liberation, and I have never separated education from liberation,” she said.

To end the lecture, moderator David Ponton III gave Davis the opportunity to provide the audience with words of encouragement and advice on how to continue their activism.

“What you should do is what you feel most compelled to do. There is no formula to determine how people express their activism. I think that people should combine a sense of their own potential and what they have to give,” Davis said.

“Let’s join hands and let’s do this together.”