Secrets of the acai

The Amazon rainforest is a dark, wet and vast melting pot of the greatest biodiversity found anywhere on Earth. Its 3.18 million square miles contain about one-fourth of the world’s plant and animal species. Amid this awe-inspiring wilderness, an innocuous little berry has been found to have some very amazing properties. Scientists have discovered that a dark purple berry found growing in the Amazon floodplains has the ability to kill human cancer cells.

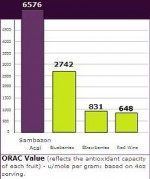

The berry – Euterpe oleracea or açaí (pronounced ah-sigh-ee) – has a higher concentration of antioxidants than any other known fruit. Specifically, most of the antioxidants in açaí berries belong to a group called polyphenols, according to Web site pubs.acs.org/journals/jafcau.

Antioxidants are essential to life because they combat the proliferation of free radicals in the body. Free radicals are a class of molecules that are highly reactive because they have an unpaired electron. Basically, they can react with – and destroy – any molecule in your body, including DNA. They contribute to liver damage from alcohol consumption, and their presence in cigarette smoke is the main reason that it gives you emphysema.

Free radicals are constantly formed in your body from exposure to smoke, sunlight, pollution and many other hazards. Many types of cancer are the result of free radical interactions with DNA. (See the graphic at the bottom of this page for further explanation.)

It’s interesting to note that açaí berries will help to destroy cancer -causing agents in the person who consumes them, but new research shows they might actually help to destroy the cancer itself. A recent study conducted at the University of Florida (UF) tested the effects of individual antioxidants found in the açaí berry on human leukemia cells in a culture. It was found that the açaí berry’s antioxidants caused apoptosis (cell death) in the cancer. The most effective antioxidant killed over 80 percent of the cancer cells.

Stephen Talcott, an assistant professor at UF’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, cautioned that this does not mean that açaí berries are necessarily a cure for cancer.

“This was only a cell-culture model, and we don’t want to give anyone false hope,” Talcott said.

Further research is needed to determine the berry’s cancer-killing abilities in the complex environment that is the human body.

“We are encouraged by the findings, however,” Talcott said. “Compounds that show good activity against cancer cells in a model system are most likely to have beneficial effects in our bodies.”

Due to these findings, açaí berries have become a popular health food in the past few years, usually in smoothie form due to their highly perishable nature. This has led to increased açaí farming in the Amazon region.

For now, agroforestry, the coupling of agricultural and natural environments, is the main technique used to grow the berries. Environmentally, this technique has a very low impact, but Yale University graduate student Jen Lewis says that may not remain the case. She has been studying the effects of açaí farming on migration and economics in Belem, Brazil.

“Currently, this is an experiment in trying to sustainably manage a forest product in the face of internationalization,” Lewis said. “The question is ‘Who will retain power (over) that production scheme? Will it be small holders, or will it take the fate of say, rubber?'”

The general policy throughout the twentieth century has been to exploit every resource discovered in the Amazon with little thought of the environmental impact. Because of this gross irresponsibility, about 16 percent of the rainforest has been irretrievably destroyed, and we continue to deforest about 1 percent of the Amazon annually. This rate increases every year, and species that haven’t even been discovered are being completely wiped out every day.

Given that almost every form of medicine known to pharmacology is derived from a natural source, the implications of this destruction are impossible to assess. No one can guess what potentially useful biochemical compounds have yet to be found by scientists, or how many have already been destroyed, along with the species that harbored them.