USF’s Fowler Avenue ‘isn’t going anywhere’ despite NIL changes

Corey Staniscia didn’t need a court ruling to see where college sports were headed.

Long before a federal judge approved the House v. NCAA settlement on June 6, Staniscia saw what was coming — a future where schools, not just collectives, could pay athletes directly.

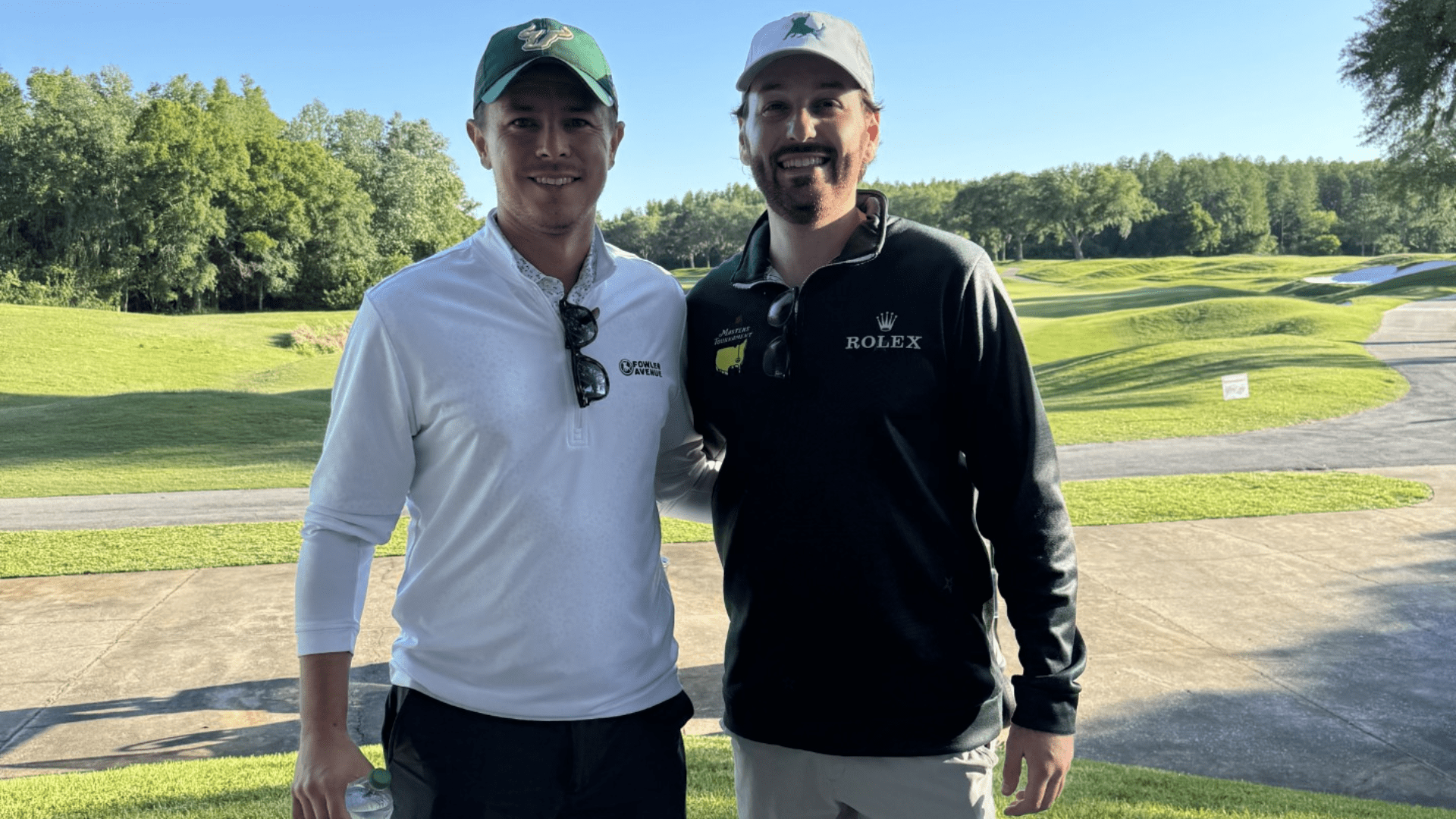

So, as the CEO and co-founder of the Fowler Avenue Collective — USF’s name, image and likeness collective — he and his team mapped out every scenario they could imagine.

The team braced for court delays, shifting regulations and the possibility that the entire settlement could collapse.

With athletes able to receive payments starting on Tuesday, collectives like Fowler Avenue face new questions about their role in athlete pay, oversight and support.

And while many collectives may fade away — especially at smaller programs — Staniscia said Fowler Avenue “isn’t going anywhere.”

Still, he believes the new model set by schools and the NCAA is “not sustainable.”

Related: Kelly says USF will be an ‘aggressive’ House v. NCAA settlement adopter

A new era for collectives, but not the end

Staniscia has seen the growth of NIL up close since its birth.

From 2019 to 2020, he helped write Florida’s initial NIL law as chief legislative aide to Rep. Chip LaMarca, the sponsor of the state House bill.

He co-founded Fowler Avenue in 2022, and said his role in supporting USF athletes has evolved ever since.

“I think a lot of people maybe just didn’t care about, or didn’t know or didn’t even want to know… what we do, and it’s not just paying athletes,” he said.

The collective will continue to focus on the services it has provided for years, helping players manage real-world logistics — like setting up businesses, handling taxes and securing legal and insurance support.

“That stuff in the background … it’s been us who’ve been doing that,” he said.

Is the NCAA to blame?

Even as schools prepare to make payments, Staniscia said the governing body often avoids labeling athletes as employees — something he views as an evasive move.

“That is the hill that the NCAA will die on,” he said. “To treat an athlete like an employee when they really are.”

Staniscia said the NCAA’s refusal to take responsibility for athlete misclassification and pay hasn’t changed.

“There’s been a gaping hole because of their lack of leadership… probably in the last 40 years,” he said. “They’ve been hiding their head in the sand.”

Under new NCAA rules, any NIL contract worth more than $600 must be reported to a national clearinghouse, which is run by the auditing firm Deloitte.

Staniscia said he finds that alarming.

“It is very strange and uncomfortable to ask a private citizen to disclose their private contracts, to have that approved or denied,” he said. “Who are they to say what’s fair market value?”

Staniscia said all Fowler Avenue contracts were signed before the June 11 threshold, and do not currently fall under the new rules.

Related: USF men’s basketball rounds up roster with latest commits

Was NIL the problem?

Staniscia said he often sees critics blaming NIL and the transfer portal for disrupting college sports. But he doesn’t see chaos — he sees balance returning.

“When you see an institution making … millions of dollars a year, and the athletes making none, there was an imbalance,” he said. “Now the power and the balance of money and things like that are coming back down to earth.”

And while NIL has stabilized things for many athletes, Staniscia said non-revenue and Olympic sports could be under increasing financial strain as schools shift money toward athlete revenue sharing.

He doesn’t think those programs should be cut — but he does think they need to be more affordable.

“I think you’re going to see some of those sports, you know, have to come back down to earth,” he said.

Nutrition programs, scholarships, strength training and travel all cost money. When those sports don’t generate enough revenue, Staniscia said that the burden becomes harder to carry.

To address this, he suggested that schools consider more regional scheduling to keep programs alive and affordable.

Instead of sending teams across the country, they could build competitive slates closer to home.

That way, Staniscia said, football’s financial pull doesn’t end up “dragging down everything else.”

As the settlement starts paying athletes, Staniscia said Fowler Avenue will stay focused on what its been doing since the start — supporting athletes where the system may still fall short.