Fair trade event focuses on Starbucks’ coffee beans

Organizers holding a Fair Trade Awareness workshop outside the Phyllis P. Marshall Center on Monday night had a message for students worried about the ethics of purchasing Nike sneakers and Gap khaki pants: They need look no further than their daily cup of Starbucks coffee.

The workshop – part of a campaign started by Students for Social Justice to increase knowledge about the mechanisms behind global trade – focused on multinational corporations’ exploitation of small-scale Ethiopian farmers.

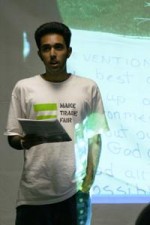

“Fair trade is about giving farmers and producers a fair price for their labor,” said Students for Social Justice (SSJ) President Salman Khan. “(Fair Trade) provides a sustainable solution to poverty, it is a source of community development, gender equity and even protection for the environment.”

Khan encouraged a crowd of more than 40 people to buy products sold through fair trade agreements, which provide better wages for the farm workers by directly linking them with consumers and cutting out the middleman: multinational corporations such as Starbucks and Nestle that reap the greatest profits.

“Why fair trade?” Khan said. “Because the majority of the world population is living in poverty and the majority of those people are farmers.”

According to Khan, farmers earn too little from their labor to feed their families, provide them medical care or give them access to education.

“We promote human rights, social justice and economic stability,” he said. A poster to his left read, “If hard work were such a wonderful thing, surely the rich would have kept it all to themselves.”

Fair Trade Awareness is part of SSJ’s Farm Awareness Week, which organizers said aims to raise public awareness about farm-working communities – what they do for the economy and the hardships they endure.

The documentary Black Gold, which focuses on an Ethiopian farmer’s attempts to sell the coffee in free trade agreements, was screened during the event.

It followed Tadesse Meskela – general manager of the Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union in Ethiopia – in his quest to find more higher-paying buyers for the coffee beans he produces.

Ethiopia, which is the birthplace of coffee and the largest producer of the beans in Africa, depends on coffee for about 67 percent of its export revenue, according to the documentary.

Meskela’s union buys coffee from 101 cooperative farms employing 74,000 workers and resells it to giant international corporations in an attempt to garner greater compensation for the poverty-stricken growers.

Despite his attempts, the profit he made for the people falls below the amount they need to meet standard living conditions.For example, while a cappuccino costs more than $3 at Starbucks, an Ethiopian farmer might earn 23 cents for each kilo of beans produced.

“57 cents would change our lives beyond recognition,” said a farmer in the documentary.

The film emphasizes the discrepancy between the two worlds – producers and buyers – by contrasting the poor living conditions among Ethiopian farmers and their struggle with images of the hyper-consumeristic culture of the West.

Images of women picking poor-quality coffee beans and earning less than half a dollar a day in Ethiopia follow a World Barista Championship event in Seattle, where wealthy companies compete to make the best coffee. A segment of the film on a therapeutic feeding center in the region of Sidama, where natives starve from a growing famine, is followed by images of New Yorkers sipping lattes.

At the end of the film, event organizer Paola Gonzalez encouraged the audience to purchase products that have the Fair Trade Federation mark and to ask for fair trade coffee brews at Starbucks.

“Something can change in the Tampa Bay community and it can start here at USF,” she said.